3 Photographers who transformed Polaroids into fine art

Polaroid today is marketed as an easy (yet expensive) way to recapture everything that has been amalgamated into the word “vintage.” Consumers want to synthesize what they feel like it was to live in the past: a dreamy grain-filled paradise that had a greater sense of glamour and taste. Polaroid has quite successfully expanded its brand into accessories and fast fashion merchandise for its increasing line of primary colored plastic cameras. But Polaroids don’t have to reflect what it must feel like to hallucinate inside an urban outfitters. This accessible medium has been transformed over the years to make beautiful, groundbreaking work. Here are 3 photographers who used Polaroids to enhance their voices and made their mark in the landscape of photography.

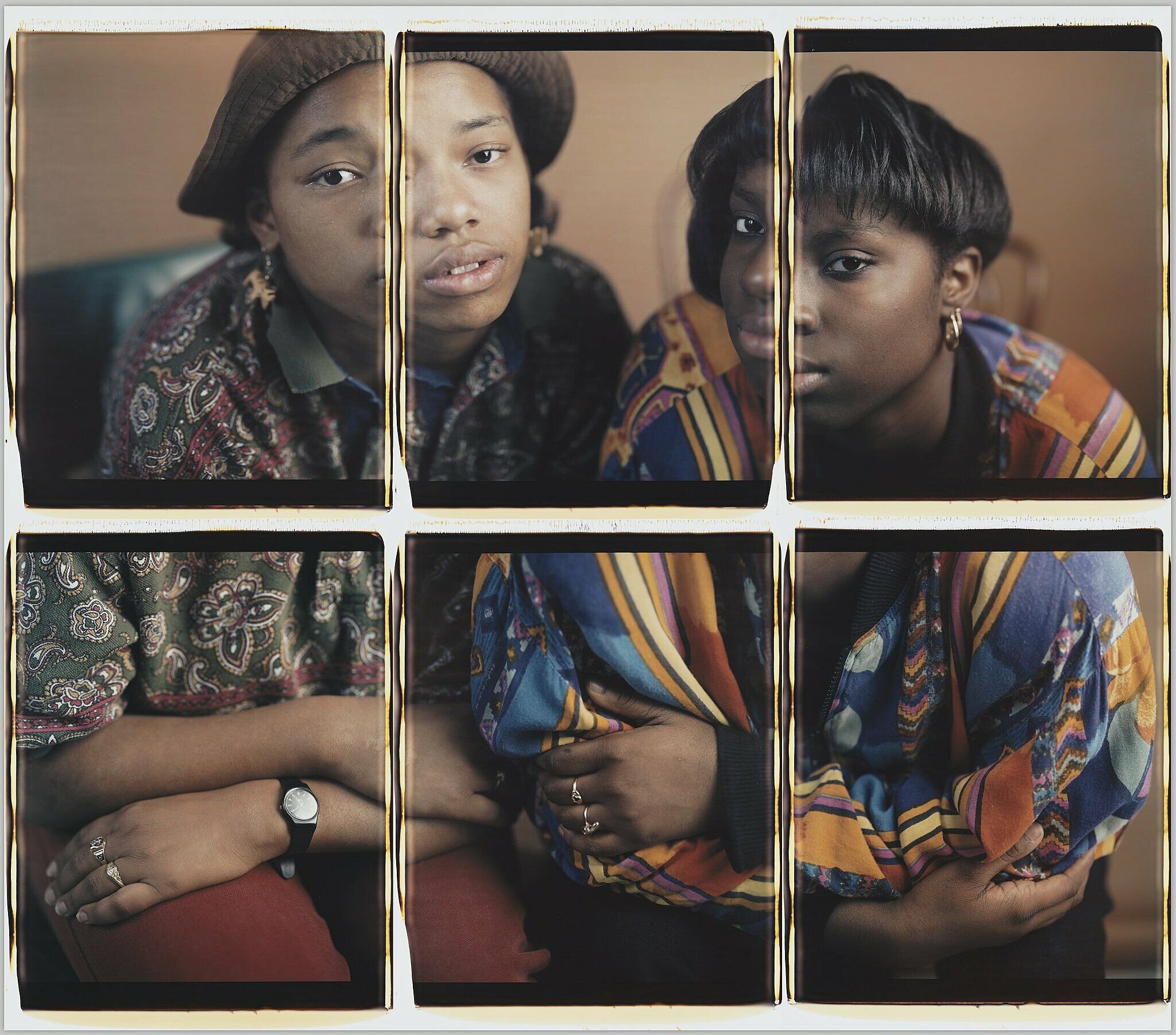

Dawoud Bey

Dawoud Bey (born 1953) is an American photographer and educator born and raised in Queens, New York, who studied photography at the School of Visual Arts in New York City.

Dawoud Bey's photography is deeply rooted in his personal philosophies and desire to represent marginalized groups of people underrepresented in mainstream culture. His work focuses on issues of identity, race, and the history of photographic representation in America. Bey’s body of work is largely built from photographing people from his own community and those who have been other-ed, excluded from the white monolith known to be the art world.

Bey has stated that his approach to photography is informed by a desire to create images that "reflect the complexities of the people and the world around us." He believes that photography has the power to challenge stereotypes and reshape our understanding of the world and that it could be used as a tool for social change.

Throughout his career, Bey has photographed various subjects, from teenagers in Harlem to residents of the American South. He is particularly known for his large-scale color portraits, which capture the nuances and complexities of his subjects' personalities and identities. He often works in collaboration with his subjects, encouraging them to pose and express themselves in ways that feel authentic to them.

Bey’s transitioned to Polaroid after a long career shooting 35mm street photography. As his contemporaries began to find a similar rhythm in street work, he questioned the ethics behind a practice that he felt disadvantaged the subject in favor of the photographer. This power indifference began to represent the same subjection he spent his whole career dismantling. In 1988 he began to use a tripod-mounted 4X5 camera with Polaroid Type 55 Positive/Negative. This allowed him to slow down his process and reach a personal intimacy with his subjects that transcended beyond the instantaneous street photo. Using this camera, he gave his subjects the instant photo and retained the negative to make a large print. This kind of mutually beneficial transition seemed to fit more in line with the ethical lines Bey set for himself early in his career.

Bey’s personable methodicalness reached a new level in 1991 when he began shooting a 20x24 inch, 6 foot tall, two hundred pound Polaroid camera. This camera took two people to operate (The photographer and the technician) and was made available to him through Polaroid’s Artist Support Program, a dated initiative that provided Polaroid cameras to artists to the likes of Andy Warhol and Robert Rauschenberg to test the cameras and provide feedback.

For eight years Bey photographed friends and a series of teenagers he met through high school residency programs. Bey sights Rembrandt as his primary inspiration for this work, a Dutch painter he did a report on in the sixth grade. He says, “the heightened sense of the individual, the warm brown background, the single light source,” all spoke to him and informed the photos. The photos were presented as diptychs and multipanelled layouts. The work brought a certain dynamism and complexity that was lost in the fixity of a singular photo. Instead of freezing his subjects in time, Bey was able to convey the multifaced and ever-changing nature of his subjects through scale and duplicity. Dawoud’s work was built to expand the viewers’ understanding of the subject and reframe their preconceived notions of what things like beauty, depth, family, and race looked like inside the American landscape.

20 x 24 Large Format Polaroid Camera ©www.hathawaygallery.com

Watch Adam D. Weinberg interview Dawoud Bey here.

Check out Dawoud Bey & Carrie Mae Weems in Dialogue April 4–July 9, 2023, at the Getty Center here.

Visit The MET to see Rembrandt in an ongoing exhibition, “In Praise of Painting: Dutch Masterpieces at The Met.” here.

Walker Evans

Walker Evans (1903-1975) was an American photographer born in St. Louis, Missouri. He was renowned for his documentary photography, which captured the essence of American life in the first half of the 20th century. In 1935, he became a staff photographer for the Farm Security Administration (FSA) where he created some of his most iconic images, which documented the lives of rural Americans during the Great Depression. His photographs captured the struggles and hardships of ordinary people, and his keen eye for detail and composition helped to elevate documentary photography to the legitimized art form it is today.

Evans’ work invoked a sense of social realism and helped to shed light on the lives of ordinary Americans during a time of poverty, hardship, and social injustice. His photographs captured not just the physical landscapes of America, but also the psychological and emotional landscapes of its people. At their best, these black-and-white photos unearthed a quiet disillusionment inside Americans during this time of objectively harsh reality. Evans often used the soiled faces of children, the elderly, and the impoverished American family to reflect both the culture of profound loss and the tight-knit communities that sprung out of pain.

©Walker Evans

One of Evans' most famous works is his series of portraits of sharecroppers in Alabama, which he created in collaboration with writer James Agee. The resulting book, "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men," was published in 1941 and is now considered a classic of American literature and photography.

A lesser-known fact about Evans is his wide-ranging body of Polaroid work, in part because it was such a radical divergence from the brooding grit of his documentary photos. Evan’s fascination with color Polaroids came at the end of his career in the 1970s when he began experimenting with an SX-70. Drawn to the instant gratification and convenience that Polaroids offered, Evans photographed intimate portraits of artist friends with close-ups of their faces and hands.

©Walker Evans

The Polaroids Evans took have an emptiness and intensity that connects them to his black and white work, with subjects looking disassociated, almost like walking husks in Invasion of the Body Snatchers. But slowly a new mood creeps in, a quiet brevity comes to life when Evans started photographing still lifes. He took photos of objects such as bottles, jars, tools, houses, and signs exploring the textures and details of everyday objects.

Evans teaches us a lesson about how time and age work to inform photographs. The uncertainty, fear, and desperation from the economic downturn in the 30s is at odds with the widespread culture of individual expression, experimentation, and self-discovery of the early 70s. Walker in his late 60s is faced with a completely different cultural landscape and morphed his work to reflect it. Both the medium and the subject matter represent a sort of letting go, a more meditative body of work. Often when artists change their creative M.O., the bodies of work are split up into binaries: “This is his good stuff, this is his bad stuff.” Rather than take that approach it’s important to think of how Evan’s used his gift for representation to mark two massively formative periods, both in his life and in American history.

Check out MOMA’s 1880s - 1940s “Documenting Rural Life” collection featuring Walker Evan’s photos. Reserve timed tickets through June 2023 here.

Watch Wim Wenders talk about Walker Evans as the inspiration behind his 1974 film, “Alice in the Cities” here.

Elsa Dorfman

Elsa Dorfman (1937-2020) was an American portrait photographer known for her large-format Polaroid camera portraits. Using the same camera Dawoud Bey used, the 20 x 24 Polaroid she said to have nagged the company relentlessly for, Dorfman built a body of work spanning three decades. Elsa would charge $50 for a portrait session (an extremely modest price considering the film type) and shoot about 60 frames a year. The Artist (who would never identify herself as such) described photography saying, “The camera is like a fork or a spoon. It’s an instrument you eat your soup with. It’s not the soup.”

Her work often focused on the ordinary people she encountered in her everyday life, such as families, friends, poets, and musicians. Dorfman's portraits often feature her subjects in relaxed and intimate poses, with a focus on their personalities and quirks. She was known for her ability to capture her subjects' essence in a single image. Dorfman's work expresses a deep appreciation for the people in her life and the moments she shared with them. Her portraits are often characterized by a sense of warmth and familiarity as if the viewer is being invited into the subject's world. She talked of the Japanese word “sonomama” in her work, meaning complete naturalness and attention, a quality she felt she had in her subjects.

Elsa had a practice of showing her subjects two photos. The one they liked, they would take home with them. In her work, Elsa seemed more in service to the subject than the photo itself. She wanted her subjects to feel comfortable, at home, allowed them to smile, and the interaction was one of mutual satisfaction. This kind of service both helped coin the work Elsa made and proved to be a critique of hers. Some people read her photos as nostalgic superficiality, rather than crafted work. People have labeled her work as repetitive or formulaic. Because she often used the same camera and similar settings, people argue that her images look similar to one another and lack variety. However, everything that is supposedly wrong with her photos can be seen as the quintessential element of the work. That this repetition is actually part of the charm, and it adds to the sense of intimacy and familiarity that characterizes her portraits.

For some Elsa’s Polaroids and handwritten inscriptions are merely some in a long line of uninventive studio photography. For others, her work feels personable, inspired, and uniquely her own. Was Elsa the woman who hung out with Robert Frank, and Susan Sontag but would never be one of them? Or was she exponentially cooler because she was never trying to be?

Check out Errol Morris’s documentary on Elsa, “The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography” here