Forgotten Film Types: The Appeal of Disc, 126, and 110 Formats

The two most popular formats in film photography are undoubtedly 35mm and 120. 35mm is the framework for what we view to be a standard photograph. Using either a 28mm lens or a 35mm lens, 35mm photography is seen as an extrapolation of how our eyes view a scene in front of us. Pioneers of 120 have inspired photographers to use the form in still lifes, street, and most commonly portraiture. The image of a single subject framed through a 120 camera is something any of us who shoot film can easily picture in our mind’s eye. So what film formats have fallen to the wayside in the midst of this overwhelming popularity? What makes these less palatable for photographers and should we still find value in them today? Let’s explore three uncommon film formats: Disc, 126, and 110.

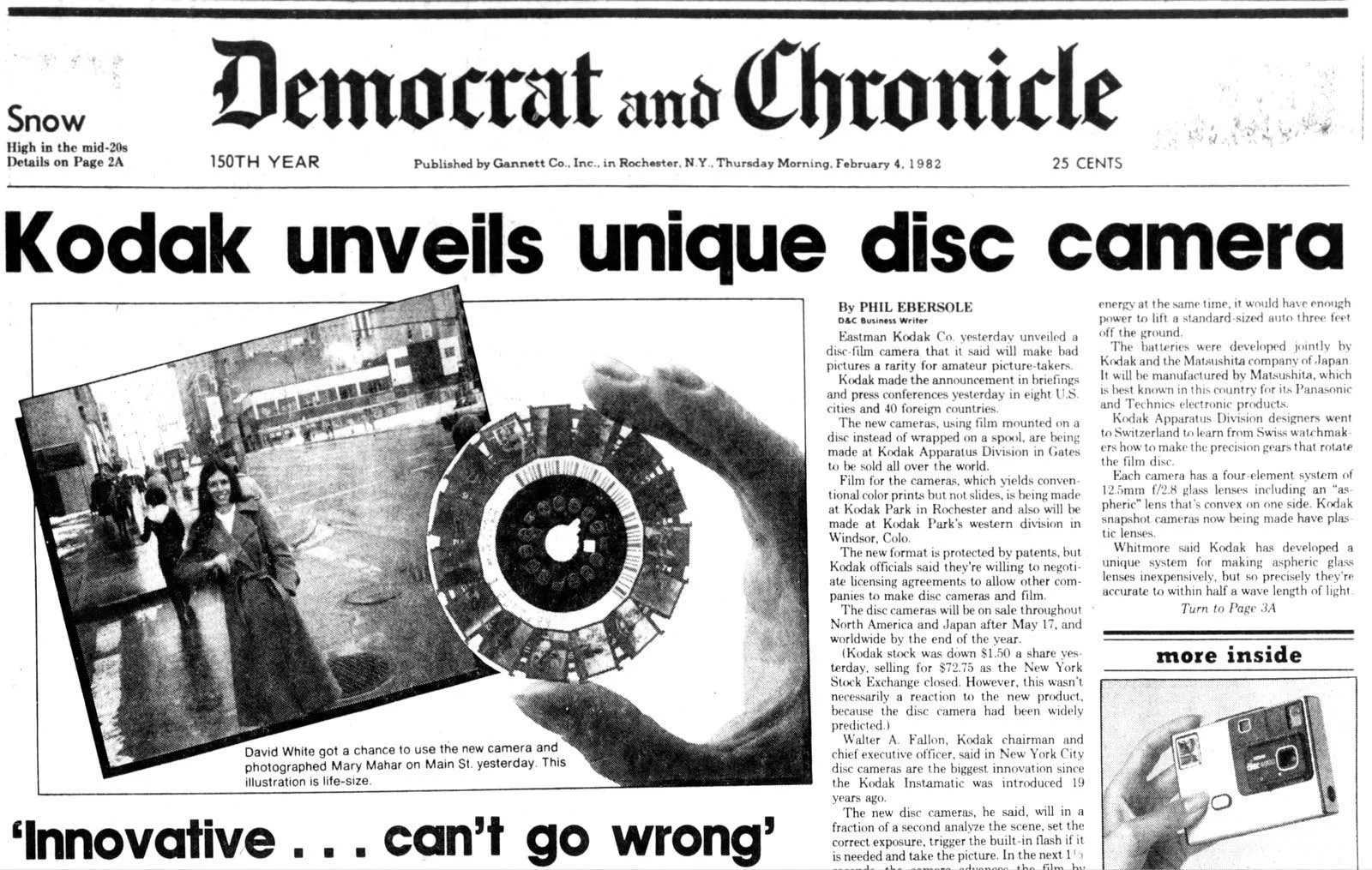

Disc

How does it work?

One thing you can’t say about Disc cameras is that they’re not unique. Compact and fairly simple in design, these cameras are generally flat, a little larger and thicker than a deck of cards, with a rounded or square shape. On one side, you’ll find the lens, often covered by a sliding or flip-down cover that also serves as the camera's on/off switch. Beside the lens, there’s a small flash unit and a light sensor. The other side of the camera usually has a clear plastic window to see the film disc inside.

The film itself is encased in a thin, round cartridge about the size of a hockey puck. Inside the cartridge, the film is arranged in a circle with 15 individual, pie-slice-shaped frames around the edge. To load the film, you simply drop the whole cartridge into the camera, close the back, and you’re good to go. When you advance the film, the disc rotates inside the cartridge, moving each frame into position behind the lens.

This camera has a simple point and shoot design. Point the camera at the subject, fire the shutter, and the photo is taken. The flash fires automatically and there are no manual settings you can control on this camera. On these cameras, you can usually take 15 pictures on a disc before needing to change the film.

Why it didn’t work

By Lou Jacobs Jr, Los Angeles Times July 25, 1982

A funky form factor, a novel shooting approach, and ease of use are factors that sell film cameras today, so why didn’t this one succeed? Kodak discontinued production of these cameras 11 years after their genesis in 1988 for one primary reason: quality. Each frame on disc film is only 8 x 10 mm, which is very small compared to 35mm film. This results in lower-resolution images that are grainier and less detailed. These flaws are brought to light significantly when enlarged. To make prints of these negatives that actually reflect good quality, printers at the time had to upgrade to special equipment. For most printers, this didn’t seem like a worthwhile investment so they opted for printers that worked with already standardized film formats. This drove an already teetering market campaign into the ground. The ease of use was not enough to trump the objective poor quality of the images and what was predicted to be a consumer wildfire became more of a wildering trash flame.

Worth it today?

I think anyone would be hard-pressed to find a reason to shoot this camera today. Of course, there is always a world where someone digs one of these up as viral bait but beyond a recommended Instagram reel, it’s hard to see a use for the camera. One thing this camera can be credited with is what it was marketing, accessible film shooting. Its ease of use and compact design were ahead of its time and can be seen as a precursor to the point-and-shoot digital and film cameras that would later dominate the consumer photography market.

126

126 Film Negative (1970s)

How does it work?

126 cameras are extremely compact, built with a plastic film body, and are easy to use just like the Disc camera. They typically have a very simple viewfinder, a slot for loading the film cartridge, and a flash mount for attaching flash cubes. Many have a simple fixed-focus lens, although some models offer a basic zoom feature.

126 camera: ©Robert Couse-Baker via Flickr

The 126 film comes in a flat, rectangular cartridge that’s very easy to load. One side of the cartridge is completely flat, and the other side has a small circular hole where the film is exposed. The film itself is a strip of 35mm film that has been cut and perforated to fit the cartridge format. Nowadays many photographers will load 35mm film into 126 cartridges. The process is not extremely difficult but keep in mind this all has to be done in the dark because the 35mm film must be removed from its plastic casing. Additionally, 35mm has a different perforation scheme than 126 film. Without getting into too much jargon, this means if you load 35mm into a 126 camera you will have visible film perforations on every frame, and you will have to wind the advance lever several times between frames. However, this process is made easy with the FakMatic 35mm to 126 Adapter that allows you to easily load 35mm film without all this hastle.

Why it didn’t work

Unlike the disc camera, 126 film continued production until 2008, 45 years after its creation. To say it “didn't work” is perhaps untrue but it seems to have been superseded by more popular and standardized film formats. The 126 camera’s fall from popularity was nothing out of the ordinary. As time went on consumers wanted an increasing image quality that the plastic cameras failed to meet. The introduction of 35mm point-and-shoot cameras in the 1980s, for example, offered superior image quality and similar ease of use. Once digital began to sweep the market in the late 90s, only the faster, higher-quality film cameras remained profitable.

Worth it today?

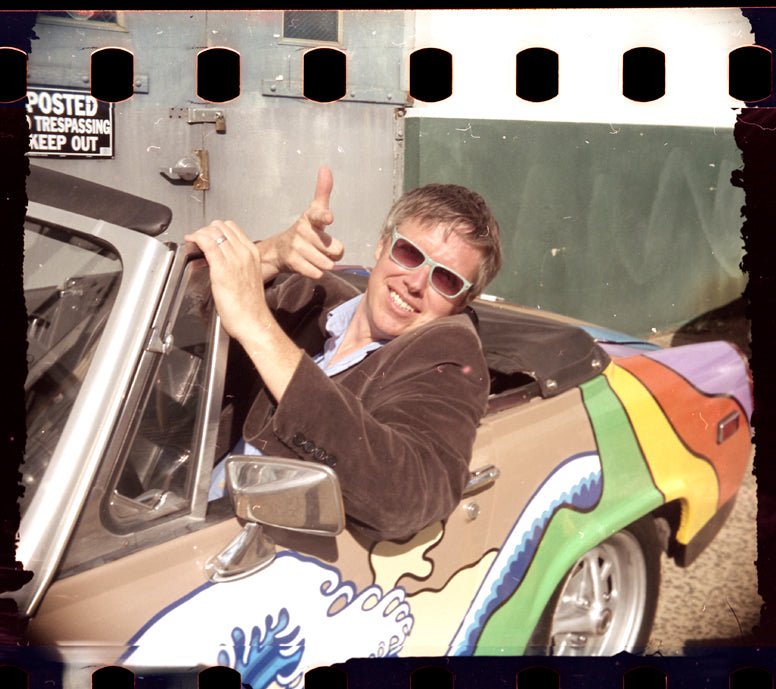

Contrary to my opinion on disc film, I think shooting 126 film would be a great idea in today’s world of film. Buying a camera and a 35mm converter would be less than $50 and would allow you to process the film at any lab. The nostalgia and gritty feel of the imprinted sprocket holes gives you an extremely unique look and could be a great alternative to a disposable camera. These images feel perfect for collage or multi-media projects and offer something nostalgic and fresh in a very oversaturated image market.

110 Film

110 cameras were designed in 1972 as the miniature version of the 126 cameras. The most significant difference between 110 and 126 film is the size of the film itself. 110 film uses a smaller 16mm film strip, compared to the 35mm film strip used by 126 film. This results in smaller negatives and, consequently, lower resolution images when compared to 126 film. 126 film typically produces square images, while 110 film produces rectangular images. Essentially, the features that made the 126 camera profitable and palatable—portability, low manufacturing cost, high automation, ease of loading, and limited lens variety—are all amplified in this camera. The 110 is extremely tiny usually with one fixed lens, some having built-in electronic flashes as opposed to the bulbs used on 126 cameras. In both cases, the goal of these cameras and film formats was to make photography more accessible to the casual user. They were less about image quality and more about convenience, simplicity, and making photography fun.

©Paul Burrows

Why didn’t it work?

Plagued with all the same issues as the cameras before, the 110 film production came to a halt in the early 2000s. Looking at all these cameras, the 110, in particular, begs the question: what is compromised for ease and convince? Consumers nowadays have an exuberant amount of expectation that cameras will provide a high image quality and will be easy to use just based on the surge of digital. Even film shooters who prefer a gritty, underexposed look with light leaks and abstract markings would be stretched to their limits with the 110 camera. Although it is extremely covert, and about the simplest thing you can shoot, consumer trends lean towards a full-body camera that shoots well exposed, familiar-sized frames.

110 example photo © Film Preservation Project

Worth it today?

110 is a film format I’d be happy to let fade into irrelevancy if it hasn’t already. Shooting on one of these cameras is an experience where you think “Huh this is pretty cool,” shoot a roll through, squint trying to make sense of your frames, then never touch it again. 110 for me serves as a fun look at the past and a unique and inventive experiment but there is no ignoring that it missed the mark for the needs of professional photographers and amateurs alike.

With all these formats it’s easy to see why they were left behind but often the most creative photos come from unexpected mediums. With the resources available to us it is absolutely worth it to try out one or all of these forgotten cameras and see if they spark a new way of creating photos. They may end up adding a nice variety to your continuing photo work.