10 Movies Every Film Photographer Must Watch

This week we asked our staff to write about their favorite movies that all involve film photography. Read all the Nice recommendations below

Amélie (2001)

“Watching Amélie (Jean-Pierre Jeunet) is like sinking into a memory foam mattress, or something akin to what the Danes refer to as, Hygge. We follow Amélie (Audrey Tautou), a chronic introvert with only the best intentions and her head perpetually stuck in the clouds, through Paris as she makes it her mission to help others. Her charity conveys her unique charm and her warm yet fastidious nature. She is perfectly fine letting her life fade away, becoming merely a gateway for other people’s joy until her recluse of a neighbor (Serge Merlin) points out her tendency to avoid actualizing her own wants and desires.

Photography becomes a largely traumatic medium for Amélie when a neighbor convinces a young her that her photos are a direct cause of violent and natural phenomena happening around the world. The medium only re-enters Amélie’s life when she finds a book full of collaged photographs and becomes obsessed with finding the owner. Through photos, Amélie finds the first real connection of her life and starts chasing an overwhelming feeling in a heartwarming quest, you’re not soon to forget.'“

— Gabe Ginsburg

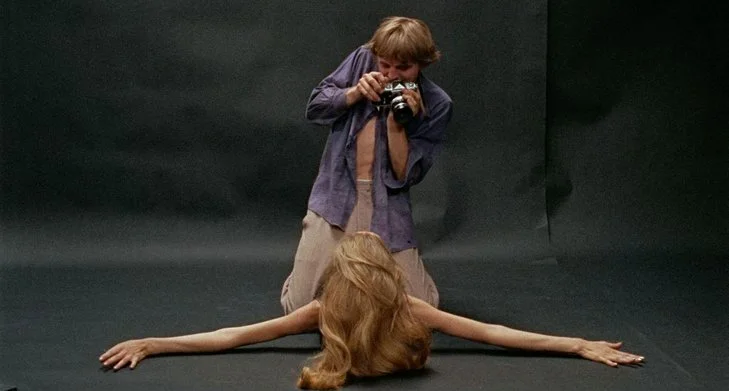

2. Blow Up (1966)

“Michelangelo Antonioni famously stated to critic Roger Ebert in a 1969 interview that his film Blow Up was “Not about a murder, but about a Photographer”. The film follows 24 hours in the life of Thomas, an up and coming photographer in 1960s London. He makes his money photographing fashion models, but he’s more interested in photographing the working class that remains alienated from the swinging mod counter culture scene he seemingly navigates with ease. Thomas discovers in the background of one of his photos a man hiding in the distance. Upon enlarging the photo he sees what appears to be a pistol in the man’s hand. Initially believing he saved he saved the life of the man in the foreground, further inspection and enlargements of the photos show something else hiding in the foliage, a dead body.

Central to Blow Up’s concerns is photography’s (both still and cinematic) ability to capture something which the device’s human operator is unaware of, and in doing so its capacity to shake us from our static solipsism by demonstrating that the seemingly inert world outside of us is in fact independent and unconstrained. More pressing though is the subsequent logical conclusion the film arrives at, that despite the photographer’s ability to capture immediate reality, we are unable to discern an immediate truth from it. Photography ultimately may offer us the opportunity to see the world with greater clarity than we ever might have before, but we are still left ultimately with an abstraction that beckons towards infinite unknowns rather than digestible clarity. And yet if there is anything certain that can be taken away from Antonioni’s mystery, it’s that even without the promise of answers, people will always impulsively look for them in the grain.”

— Zak Goodwin

3. Calendar (1993)

“Calendar is a 1993 film by Atom Egoyan. It is a story told in pieces that shows the dissolution of a marriage on a trip to Armenia to photograph churches for a calendar. We see the story unfold behind the lens of the camera as the photographer watches his wife translate what their driver is telling him about the history of the sites they visit. While the driver and the photographer’s wife experience the places and create a bond, the photographer (and in turn the viewer) are trapped behind the camera. In wide shots we watch what the photographer sees. He will not let himself step away from the viewfinder and will not walk into the landscape because he is unwilling to uproot the camera from its tripod or miss a moment where the light is perfect. The film switches between these scenes at the churches to vignettes from each month of a single year, in each scene we see the calendar up on the wall and it brings us back into the moments the photographs were taken. The film itself is unnerving and isolating. It's a personal favorite of mine and an interesting examination of a photographer's inability to live in the moment, instead he chooses to experience his life through rewatching footage of the trip and through the photographs in the calendar.”

— Collette O’Brien

4. City of God (2002)

City of God (Fernando Meirelles) takes us to war torn Rio de Janeiro where three decades of infighting has led to brutal conditions inside what most would consider an unlivable slum. What starts as children peacocking at being gangsters quickly becomes reality. We watch latchkey pre teens sharpen like knives and turn into the city’s most feared hitmen. Our protagonist Buscapé (Alexandre Rodrigues) finds himself square in the middle of what eventually becomes two warring tribes. The fighting begins as a quest for vengeance then morphs into an unyielding blood bath, feeding on its own malignancy. Buscapé knows he doesn’t want to be what’s referred to as a “hood” but is also aware of how little opportunity there is to escape the neighborhood without the large cash influxes violence provides. Although he flirts with crime, Buscapé finds a new out, Photography. We begin to see the neighborhood through the eyes of the viewfinder as Buscapé learns the language of seeing and what was once an insular crime network becomes a front-page headline for all the world to see.

— Gabe Ginsburg

5. Eyes of Laura Mars (1978)

“Eyes of Laura Mars is a 1978 thriller starring Faye Dunaway and Tommy Lee Jones. It is directed by Irvin Kershner with the story by John Carpenter. Laura Mars is a photographer whose work depicts lavishly styled models in acts of violence. As the release of her photography book nears, more and more of her associates are murdered. As each of them is killed, she sees the scenes from the eyes of the killer. She compares it to looking through the viewfinder of a camera and not being able to actually see what's really in front of her. The public blames the murders on the violence being depicted in her work. The photographs themselves are gaudy, extravagant, and graphic. Helmut Newton created all of the photographs for the film and it is evident why he was chosen to do so. His own work is often considered controversial for its violent and sexual nature. It's a really fun watch and a wonderful document of New York in the 70s. It brings into question the culpability of photographers in what they decide to “shoot” and has some glamorous darkroom and shoot scenes. Who doesn’t want to see Faye Dunaway posing with her Nikon?”

— Collette O’Brien

6. Jamel Shabazz Street Photographer (2013)

“Jamel Shabazz is fun. He is unintentionally funny I think, but wonderful nonetheless. This movie will teach a photographer to stick to a subject and form. That there is no exhausting the medium or your style. Those photographs that serve to document a culture and history that others can look back on and remember fondly is done best by him. There is a lot to take away from his work, whether it’s your style of photo making or not.”

— Maximo Borisonik

7. One Hour Photo (2002)

“One Hour Photo, directed by Mark Romanek and starring Robin Williams, is a psychological thriller released in 2002. The film revolves around Seymour "Sy" Parrish who, on the surface, is a harmless and lonely photo lab technician. Sy becomes fixated on a seemingly perfect family, the Yorkins, as he secretly develops and prints their personal photos for years. While Sy delves deeper into their lives, the lines between reality and his own distorted perceptions begin to blur. One Hour Photo is a cult classic thriller, perfectly walking the line between campy and somber. Robin Williams’ performance is absolutely unforgettable, but my favorite aspect of the movie is that it's from the perspective of Sy working at the film lab. They really got everything right, from the equipment they use in the lab, all the way down to Robin Williams’ fascination with Mrs. Yorkin’s Leica Minilux. In my opinion, this is a very easily accessible movie and infinitely re-watchable.”

— Dylan Permuy

8. Pecker (1998)

“Pecker, released in 1998 and directed by John Waters, is a quirky comedy that follows the life of Pecker, a young and eccentric amateur photographer from Baltimore who accidentally achieves overnight fame in the art world. As he navigates the complexities of sudden stardom, Pecker's genuine passion for photography and capturing authentic moments is evident. I think many photographers can relate to the struggle of balancing artistic integrity with commercial success, the challenges of navigating the fine line between observation and exploitation, and the desire to capture the raw essence of life through their lens. While this movie certainly won’t be for everyone, I think that plenty of photographers can get behind this. That being said, if you aren’t familiar with John Waters’ movies, just know that to describe this movie as “crude” would be an understatement.”

— Dylan Permuy

9. Streetwise (1984)

“Streetwise is comprehensive. It is television interviews, documentaries, photographs, poetry, and storytelling at its superb. It is a world beyond the film itself, an ever unraveling coil of story. A watch will teach you everything you need to know about photography. Memorize it and study it like your life depends on it.”

— Maximo Borisonik

10. YI YI

Over the course of the film each character in the middle class nuclear family at the film’s center has been facing their own emotional growing pains. They are all in their own way trying to escape the ennui of modern life, struggling with the complications of day to day existence, trying to find harmony in the chaos. Then there’s Yang Yang, their precocious 9 year old son simply trying to get by in primary school and enjoy his childhood. On the way to school one morning, he asks his father “I can’t see what you see, and you can’t see what I see. How can I know what you see?”. His father offers him a literal solution to a philosophical quandary, and responds “That’s why we need a camera”.

Yang-Yang’s photos allow a chance for their subjects to step outside of themselves, to literally see a part of themselves they cannot see while offering a reminder that while they are stuck in their own personal experience, other people can show them the things about themselves they didn’t realize or appreciate. Likewise his film reminds us that life though emotionally challenging and full of seemingly unsolvable questions and dilemmas can at least be better appreciated in its universal cycles and shared experiences. Inevitably every person will attend a wedding, pay respects at a funeral, celebrate a birth, experience their first love, some kind of personal rejection, inevitable disappointment, and a lot of emotional uncertainty. But there’s something to be said that these experiences are universal, that we’re going through these things together.

— Zak Goodwin